When The Met began planning how to celebrate Hispanic/Latinx Heritage Month, discussions soon turned to naming conventions. What label is inclusive yet nuanced enough to encompass the range of cultures that have origins or ties to Spanish-speaking countries? Hispanic? Latino, Latine, or Latinx? While we cannot synthesize Hispanic/Latinx culture into one label or experience, we can gain insight into the ways it shapes individuals’ identity and experiences with the world around them.

Here, we've asked four contemporary artists to speak about how their cultural background impacts and is reflected in their work. Their responses touch on a variety of themes, from colonialism and immigration, to the nuances of race, bodies, and the appropriation of narratives. Each artist provides a glimpse into their lives, their experiences, and their art.

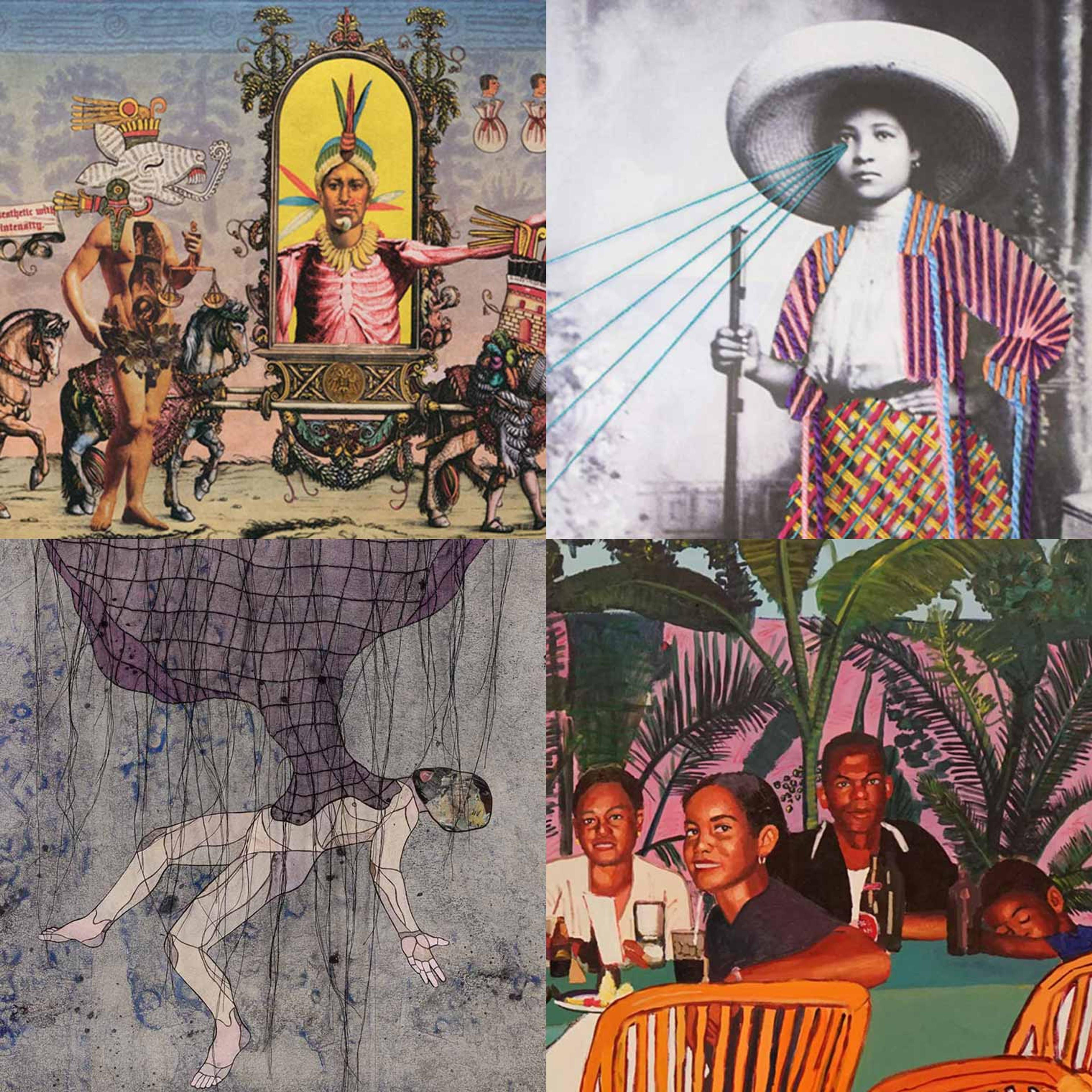

Enrique Chagoya

I often paint self-portraits representing such genetic mix in my blood, through various ethnic stereotypes and gender roles. My father's family is from Teotihuacán, the famous town of the ancient pyramids near Mexico City, and my mother's family is from Zultepec. They moved to Mexico City and I grew up there until my mid-twenties.

Enrique Chagoya, The Waters of Oblivion in Mictlán, 2021. Layered acrylic ink, gold leaf, and varnish on amate paper, 21.5 x 87 in. © Enrique Chagoya. Courtesy Enrique Chagoya

My recent codex/scroll The Waters of Oblivion in Mictlán (2021) is about greed and gold sought by the Spanish conquistadors in Mexico during colonial times. It is an acrylic digital print on handmade Mexican amate paper. In that work, I appropriate engravings that describe a procession celebrating The Triumph of Maximilian by Hans Burgkmair done in Austria around the times of the conquest of Mexico. The engravings were finished after the death of the emperor Maximillian in the early sixteenth century. The gold represented in the scroll and printed with gold leaf by hand—coins, gold bricks, and jewelry—refers to my work from an Aztec Codex painted after the conquest: The Codex Tepetlaoztoc (Codex Kingsborough), which depicts taxes paid by Indigenous people to the Spanish Crown. Additionally, pre-Columbian gold necklaces, and other gold ornaments at The Met’s pre-Columbian galleries, are certainly connected to the use of gold in my codices.

Two artworks featured in exhibitions at The Met, Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas (left) and Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici (right). Left: Necklace with Beads in the Shape of Jaguar Teeth, 13th–16th century. Mixtec (Ñudzavui). Gold, H. 4 1/2 × W. 1 3/8 × D. 5 × L. 15 1/4 in. Purchase, Mariana and Ray Herrmann, Jill and Alan Rappaport, and Stephanie Bernheim Gifts, 2017 (2017.675), Right: Nicolás Enríquez (Mexican, 1704–1790). The Virgin of Guadalupe with the Four Apparitions, 1773. Oil on copper, 22 1/4 × 16 1/2 in. Purchase, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest and several members of The Chairman's Council Gifts, 2014 (2014.173)

The most important influences are two memorable and concurrent exhibitions I saw at The Met in 2018. One was of pre-Columbian objects from the Americas, Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, and the other of colonial painting Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici. The experience, more than a single object, was like no other I ever had in any museum. They had codices, featherworks, and other treasures that are extremely rare. The exhibitions were next door to each other. It was shocking to see the cultural transformation and imagine the cultural genocide of the Americas in such a brief period when comparing the two very different bodies of art in these exhibitions, both coming from the same region.

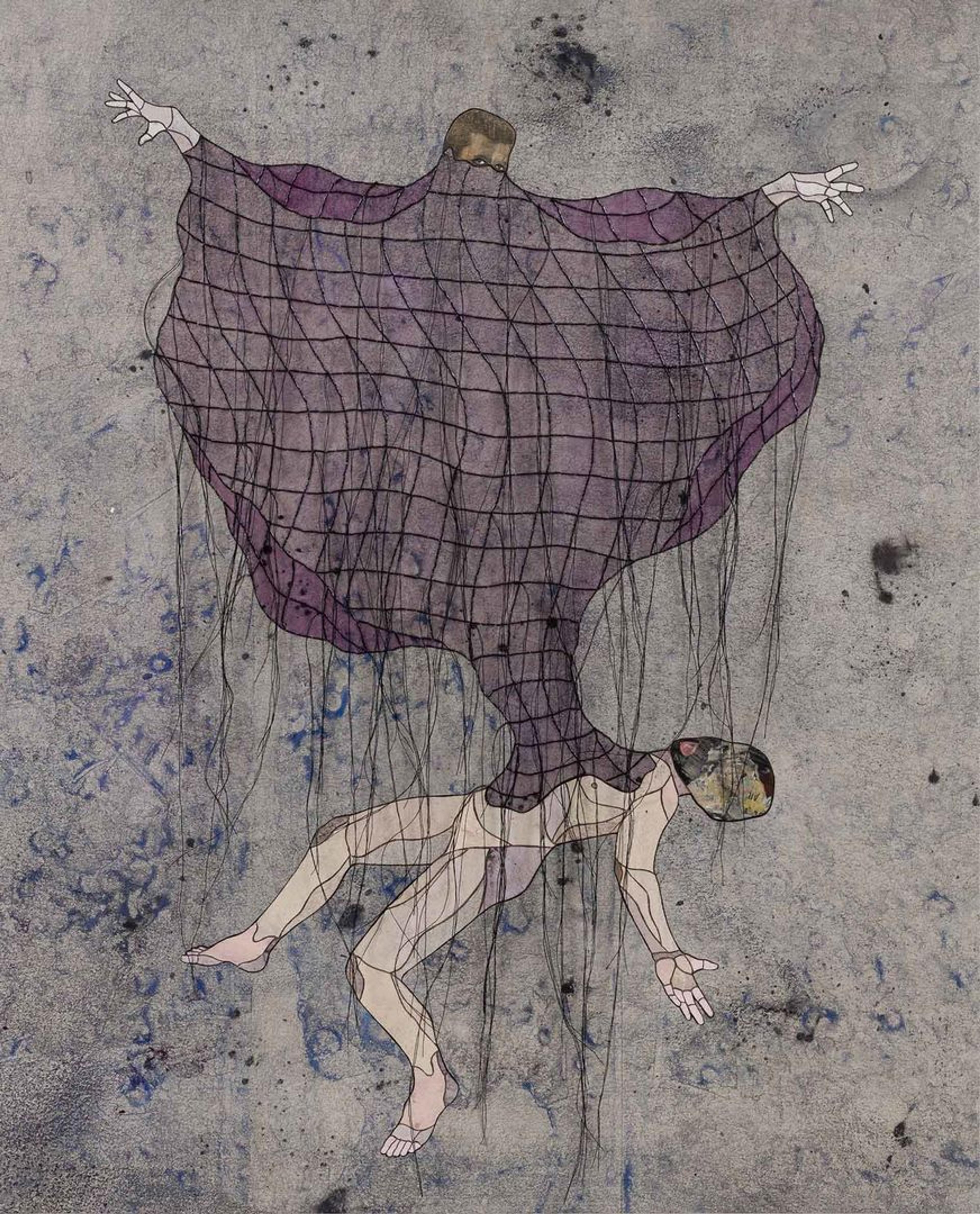

Felipe Baeza

My identity and background play a significant role in my studio practice. I was born in Celaya, Mexico, and I arrived in Chicago, Illinois, in the 90s to reunite with my parents. Then I moved to New York City in 2005 to start my undergraduate studies at the Cooper Union and have lived here since.

Felipe Baeza, Unrecognizable form,refusing to be governed, 2022. Ink, embroidery, acrylic, graphite, varnish, and cut paper on panel, 20 x 16 in. © Felipe Baeza. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

My work is often associated with queerness, fugitivity, and regeneration. However, something I have not shared in great detail is that I come from families with traditional Catholic and Evangelical Christian backgrounds. There is usually one central figure in my paper works, perhaps because in the images that I saw growing up, the body of the saint was the landscape. There was no ground.

I have been collecting and working with archival images and ephemera to create my collages for over ten years now. In a few series I collapsed images of pre-Columbian sculptures with images from fashion and erotic magazines, so The Met’s collection of Mesoamerican art is one of my favorites. The Teotihuacan-style hollow figurine with removable chest plate speaks to the ideas of fugitivity in my work, but also the body as a vessel.

Teotihuacan-Style Hollow Figurine with Removable Chest Plate, Guatemala, 5th–7th century. Ceramic sculpture, pyrite, pigment, 14 3/4 × 10 3/4 × 10 1/4 in. (37.5 × 27.3 × 26 cm). Partial and Promised Gift of Linda M. Lindenbaum, from the Collection of Samuel H. and Linda M. Lindenbaum, 2015 (2015.226a, b). Courtesy of Samuel H. and Linda M. Lindenbaum.

I’ve been incorporating foliage into my paintings for a few years now. This series reflects on migration and the bodies that never made it to the other side. There is this idea in certain Mesoamerican mythologies that when you die, your body nourishes the soil and breeds new life. Plants are a vessel through which your body can thrive. My practice today questions how we might thrive even when the landscape is not there. There are rarely landscapes in my works because the body is sometimes the only landscape that some of us have.

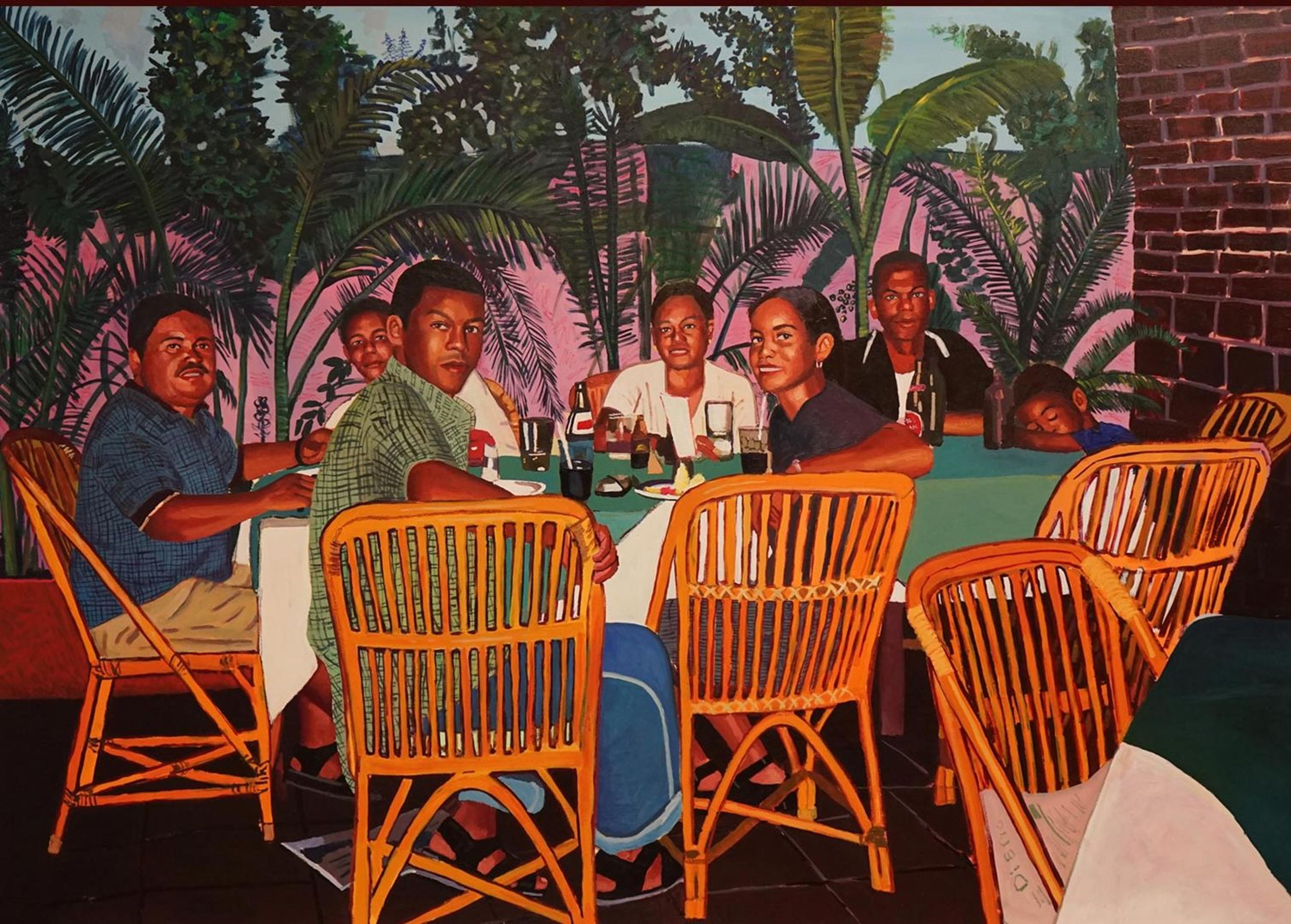

Raelis Vasquez

I was born in Mao, Dominican Republic, and I moved to the United States with my family in 2002. My work explores the tangled histories of the Dominican Republic in relation to the States and continues the lineage of imagery as protest in the Latinx and African diaspora through the representation of bodies. I reference photographs of touching moments, which I interpret in the paintings with dignity and vulnerability. The works become a practice of self-reflection and a thoughtful exploration of my own identity as an immigrant, a Dominican, and a painter.

Raelis Vasquez. La Mesa Nuestra, 2021. Oil, acrylic, and oil pastels on canvas, 60 x 84 in. © Raelis Vasquez. Courtesy Raelis Vasquez

The painting La Mesa Nuestra (2021) is based on a family photograph taken before we immigrated to the United States. I am the young boy sleeping on the table on the far right of the painting. For me, the work becomes a self-portrait that looks beyond the artist. It was also an opportunity for me to reflect on that time of innocence and naiveté—before you're forced to adapt and learn. The composition of this painting is very traditional at first glance, but invites the viewer into this moment to sit on the chair on the lower right. I wanted to subtly signal, "come sit at this table."

The colors and the space tell a story of community and culture in the Caribbean. The difference between my family’s skin tones is noteworthy because it visualizes what a Latino family of African descent looks like. Slavery in Latin American countries or in the Caribbean was different from slavery in the States. Because of the narratives the elites create in the country, the Dominican Republic becomes a very confusing place where people of African descent often think of home as Spain. The Indigenous and African parts of us get erased or negated. But when you consider it, all of these parts are yours: The African. The Spanish. The Indigenous. Growing up, I would often see the narrative of being Dominican—of being black—as something very different from my reality. That’s why I think representation is so valuable. I know what it has done for me.

"Although I love painting and studying art history, it isn’t because I see myself represented or seen."

– Raelis Vasquez

John Singer Sargeant is my favorite painter: the way he approaches his brushwork is so seamless. My relationship with his art is mostly about learning. I am interested in making people feel larger than life, giving people power on the canvas as Sargeant does. I want the figures to feel like they’re taking up a lot of space, on the canvas and in the room. By painting figures in this way, I feel like I’m being reflected. Although I love painting and studying art history, it isn’t because I see myself represented or seen. To me, the paintings become mirrors that are more honest and vulnerable.

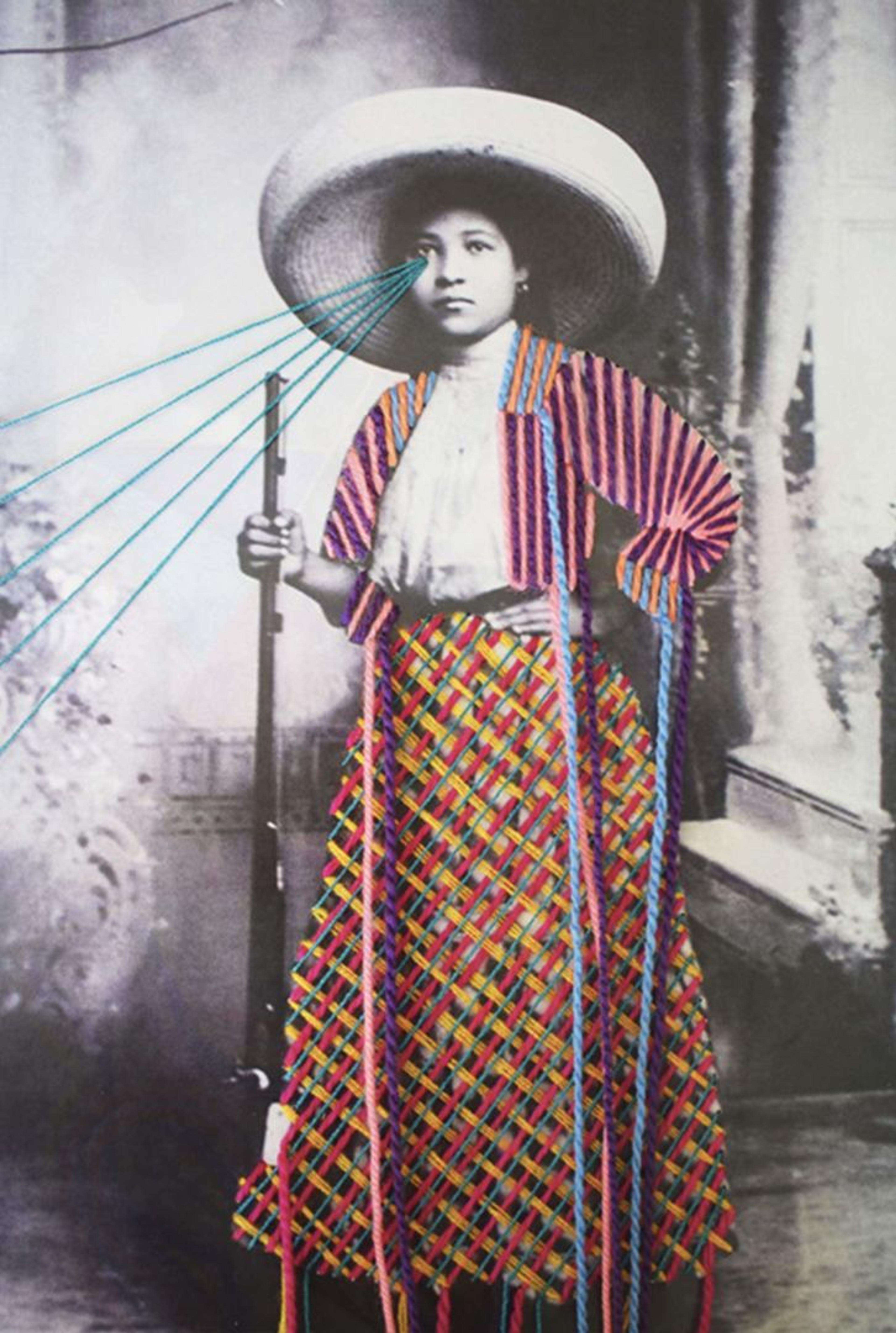

Victoria Villasana

I’m interested in historical movements that show the resilience of the human spirit. I was inspired by this portrait of a soldadera. Soldadera were women in the military who participated in the Mexican Revolution. With this textile intervention, I wanted to honor the females of the past who have been part of important movements but often haven’t had the same recognition as their male peers. I also like that this image challenges gender stereotypes.

Victoria Villasana. Soldadera. © Victoria Villasana. Courtesy Victoria Villasana

In general, I love pre-Columbian art. I really like the Aztec kneeling female figure at The Met. It makes me think of the many rituals and celebrations the Aztecs created as a part of their cosmovision.

I draw inspiration from the craftsmanship and the textile traditions in Mexico but I like to explore textile in my own way. I want to honor these ancient traditions, but I do not simply want to copy them. My approach to textile is always sensitive and intuitive. I feel textiles are a tactile, comforting element in our psyche, from the pieces made by ancient cultures to the blankets our grandmothers used to make.